For representative purposes.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

In the years prior to the pandemic, two of the largest economies in the world — the U.S. and India — cut corporate tax rates in an attempt to stimulate growth. While the pandemic caused an unprecedented shock to the economy, enough time has passed for us to evaluate the effects of these tax cuts.

The effects of tax cuts in the U.S.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was signed into law by former President Donald Trump on December 22, 2017, and went into effect from January 1, 2018.

While the act affected personal and corporate taxes, one of the most significant provisions was the reduction of the top tax rate on corporate income from 35 to 21%. Proponents of the measure held that the move would ensure that companies invest more, leading to an increase in growth and employment. The new investment would also cause an upgradation in technology and productivity, leading to an increase in wages as well.

In a recent publication titled ‘Lessons from the Biggest Business Tax Cut in U.S. History’ (published in the Summer 2024 edition of the Journal of Economic Perspectives), economists Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Owen Zidar and Eric Zwick examine the effects of the tax cut. They find that the cuts did have a positive impact on investment, with a range of studies estimating an increase in investment of around 8 to 14%. Furthermore, studies suggest that based on investment trends, there would likely have been a fall in investment if the tax cuts were not passed.

This is not to say that the tax cuts were an unambiguously positive outcome. This is a relatively small increase in investment, implying a long-run increase in GDP of only 0.9%, and an increase in annual wages of less than $1,000 per worker. This is in stark contrast to the claims of an increase in wages of around $4,000 to $9,000 dollars advanced by the Council of Economic Advisors in favour of the move. Furthermore, the reduction in tax rates imply a long-run reduction in tax revenue of almost 41%. The fiscal health of the U.S. economy has been impaired at the cost of higher profits and a marginal increase in wages.

On tax cuts in India

Tax rates for corporates were cut in September 2019 in India, with the rate for existing companies reducing from 30 to 22%, and that of new companies from 25 to 15%. This resulted in a tax revenue loss of around 1 lakh crore in 2020-21. This tax could nevertheless prove to be of net benefit to the economy if it resulted in an increase in employment and investment.

The pandemic led to severe dislocations in the labour market, leading to high unemployment. Unemployment has reduced since then, with labour force participation rates rising, particularly that of women. However, the corporate sector has had little to do with this increase. Much of the increase in employment has come in the form of insecure work, with unpaid family work showing significant increases in the rural sector. According to the PLFS, the share of workers with regular wage employment at the all-India level has fallen from 22.8% in 2017-18 to 20.9% in 2022-23. Furthermore, when comparing the periods July-September 2017 and July-September 2022, the average nominal monthly earnings of rural and urban regular wage workers displays a CAGR (compounded annual growth rate) of 4.53% and 5.75% respectively, which is barely above the rate of inflation. In real terms, rural wages for regular employment have reduced, with relative stagnation for urban wages.

This is not to say that there has been no growth; corporate tax collections have shown healthy growth since the pandemic. However, it has had little to no effect on employment or wages. Tech companies in India have recently made the news for laying off workers, rather than expanding hiring.

Furthermore, tax cuts have led to a shifting of the burden of tax collections from corporates to individuals.

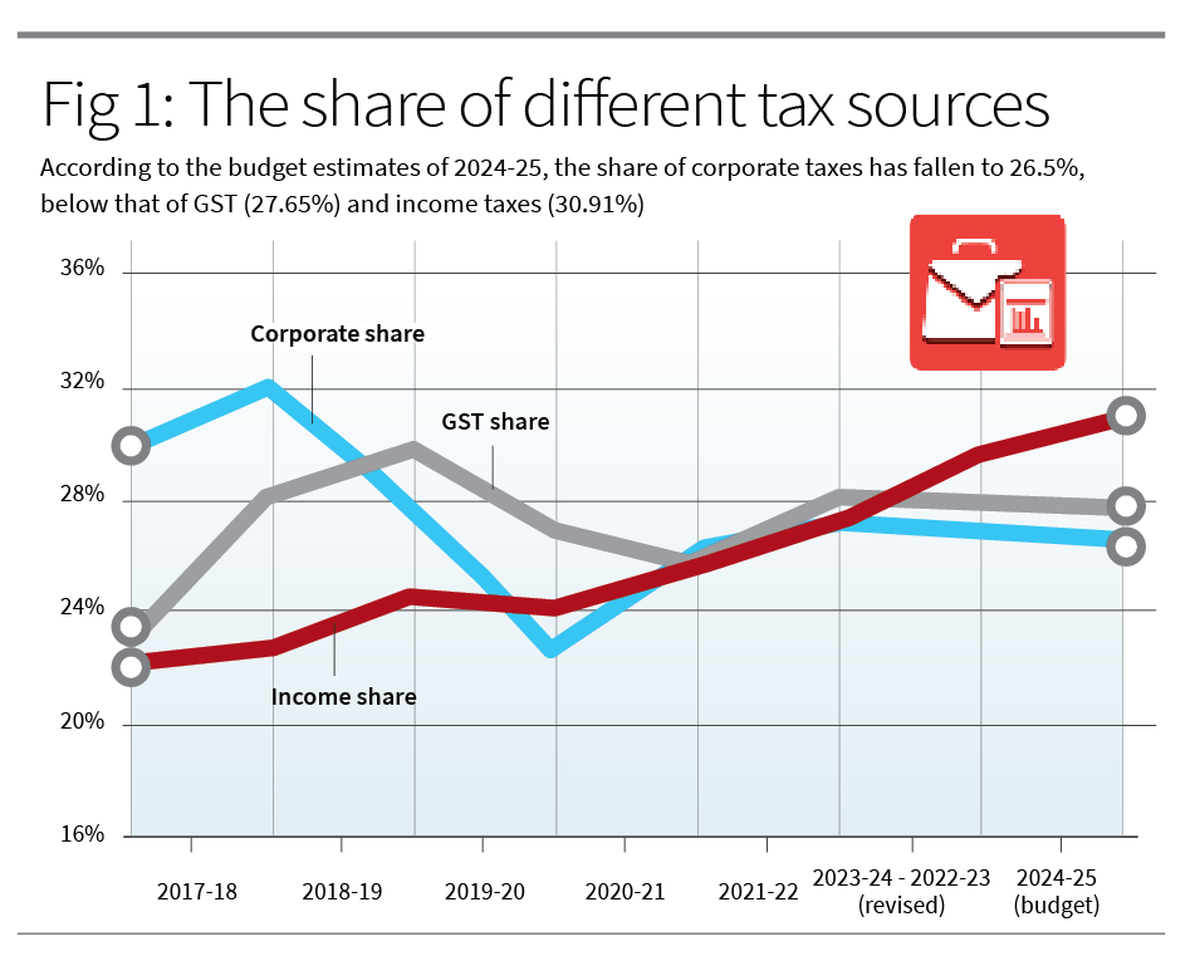

Figure 1 shows the share of three major sources of taxes — corporate taxes, income taxes and GST — in gross tax revenues of the Centre. In 2017-18, corporate taxes were almost 32% of gross tax revenues. It has fallen since then while the share of income taxes rose. According to the budget estimates of 2024-25, the share of corporate taxes has fallen to 26.5%, below that of GST (27.65%) and income taxes (30.91%).

This may explain the move of the Centre to remove indexation benefits and tax long-term capital gains, as it tries to find new sources of revenue to offset the falling share of corporate taxes.

What next?

Tax cuts would not necessarily boost investment if capital believes that the prospect of future profits are uncertain. In an economy recovering from the pandemic and from supply-related disruptions, tax cuts have exercised only marginal effects on private investment.

Tax cuts on profits do have immediate effects on income distribution. A reduction in profit taxes boosts the profits on already invested capital without increasing future investment, thus benefiting private capital while showing little to no benefits for wage-earners (who would gain only if investment raised employment, productivity and wages sufficiently).

Chodorow-Reich et al make the point that a suitable policy strategy would be to have high taxes on existing profits and increased incentives promoting future investment. These tax cuts have shown the difficulty of policy-making in an uncertain world.

Rahul Menon is Associate Professor in the Jindal School of Government and Public Policy at O.P. Jindal Global University.